[UPDATED]There was a healthy dose of outrage Sunday at Gulf Aid, the benefit concert to aid those affected by the oil disaster that occurred when the Deepwater Horizon oil well exploded. Actor Tim Robbins told the story of trying to fly over the oil spill and being denied permission, causing his pilot to speculate that BP was deciding who could fly over that airspace. While Tab Benoit and the Voice of the Wetlands All-Stars explained how the government had traded the wetlands for shipping and oil, George Porter, Jr. showed his hand, with “Give us our 50%” written in his palm.

There was a lot of concern to go around. Terence Blanchard worried about the planning that preceded the drilling of the well. “It makes me wonder if there were any contingency plans,” he said, and based on the revelations about Mineral Management Service’s cozy relationship with the oil industry—in bed with them literally, according to reports—John Legend said, “We need regulators who actually regulate.” Comedian Harry Shearer took time out from working on his documentary, The Big Uneasy, to emcee the main stage, and he worried about the effects of the oil and the dispersents on the fishermen, many of whom are out of work right now with parts of the coastal waters closed to fishing.

There was a lot of concern to go around. Terence Blanchard worried about the planning that preceded the drilling of the well. “It makes me wonder if there were any contingency plans,” he said, and based on the revelations about Mineral Management Service’s cozy relationship with the oil industry—in bed with them literally, according to reports—John Legend said, “We need regulators who actually regulate.” Comedian Harry Shearer took time out from working on his documentary, The Big Uneasy, to emcee the main stage, and he worried about the effects of the oil and the dispersents on the fishermen, many of whom are out of work right now with parts of the coastal waters closed to fishing.

“When this industry gets a blow like this, we’re losing a way of life and it’s not coming back,” he said.

While there was an unquestionable note of seriousness, Gulf Aid was also a concert, one that organizers David Freedman of WWOZ, David Torkanowsky, Barry Kern of Mardi Gras World, Sidney Torres IV of SDT, and Rehage Entertainment took from conception to execution in under three weeks. It helped that all of the headliners except Legend are New Orleans residents (Mos Def moved here recently), but it was still a significant undertaking, made more challenging by the weekend’s rains.

The money raised—a million dollars according to one unconfirmed source—goes to the Gulf Restoration Foundation, a new 401 (c) 3 non-profit that, admittedly, is still working out the method for getting money into the hands of those who need it. “People first, wildlife second, wetlands third,” Freedman says, explaining the foundation’s priorities. “It’s dollar-in, dollar-out.” Freedman is worried that if the predicted impact on the environment comes to pass, more Gulf Aids may be necessary.

“This could be a five-year effort,” he says.

But with all the music, the day itself was festive, made more so by the setting. The rain forced the outdoor stage to move into a float den, so the stage was bordered by Orpheus floats, and garage doors opened out onto the Mississippi River.

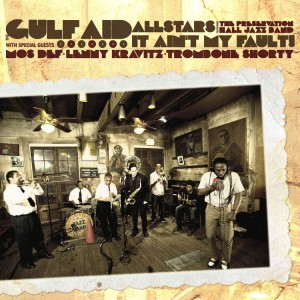

One of the highlights was the Preservation Hall Jazz Band set, which opened with the new track they’d cut under the name Gulf Aid All-Stars with Mos Def, Lenny Kravitz and Trombone Shorty. The song is a remake of “It Ain’t My Fault,” inspired by the circle of denials formed by executives from BP, Halliburton and Transocean, and Mos Def rapped over a recording of the song while members of the Hall Band added percussion. Ani DiFranco joined them for “Freight Train,” her track on the band’s Preservation album, and Cassandra Wilson (who John Legend later introduced as a New Orleans resident) sang a woeful “St. James Infirmary” with them.

The closest John Legend got to a political statement was a cover of Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes’ “Wake Up, Everybody,” but his show still had the air of timeliness. The insertion of tracks from his upcoming ?uestlove-produced album, Wake Up, gave his entire set grit and gravity by proximity. The album is a collection of covers from more socially aware times, and though his cover of Curtis Mayfield’s “Hard Times” isn’t explicitly political, the larger theme of struggling to live and love gave the song edge, and the rest of his set seemed to occupy a world of troubled times, even when it celebrated the good times in the exuberant, set-closing “Green Light.”

Recent Lenny Kravitz performances in New Orleans have stretched out with lengthy solo segments; last night, he kept it tight, playing an aggressive, hits-oriented rock ‘n’ roll show. Before “American Woman,” he said, “This was written as an anti-war song. Tonight this is an anti-oil song.”

Gulf Aid represents his most public act as a New Orleanian, and he obviously enjoyed it. During an elongated “Let Love Rule,” he called out, “I need some New Orleans brass.” Shamarr Allen, Corey Henry and Terence Blanchard joined him onstage, each taking lengthy solos that were more fun for the spectacle and the moment than their strictly musical rewards. Then he encored with an explosive version of “Are You Going to Go My Way.”

“I’m humbled to be here with this community, my people,” he said.

Update May 19, 2:50 p.m.: It seems Robbins’ concerns about BP making the rules have some truth to them. CBS News was turned away from South Pass when its crew tried to film the oil that had washed up on the coast.