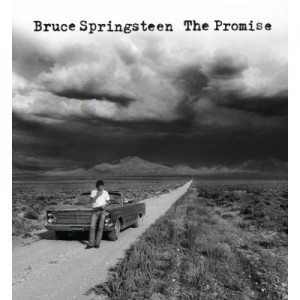

It’s impossible for me to hear Bruce Springsteen’s The Promise in a vacuum. The album’s subtitled “The Lost Sessions: Darkness on the Edge of Town,” and it’s two discs of music recorded between Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town, with only two songs from the set – “Racing in the Streets” and “Candy’s Boy” – making the final cut, albeit in different forms.

It’s impossible for me to hear Bruce Springsteen’s The Promise in a vacuum. The album’s subtitled “The Lost Sessions: Darkness on the Edge of Town,” and it’s two discs of music recorded between Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town, with only two songs from the set – “Racing in the Streets” and “Candy’s Boy” – making the final cut, albeit in different forms.

In one sense, The Promise is simply good, not great. It is, after all, a collection of leftovers and about one disc’s worth could never have seen the light of day without any injustice being done. Cherry-pick the highlights and there’s a very strong album here – but it still wouldn’t be as good as Darkness on the Edge of Town. But it’s fascinating to hear Springsteen in the process of becoming Springsteen. He passed up songs that would have sounded great on someone else’s album – and did with “Because the Night” (Patti Smith), “Fire” (Pointer Sisters) and “Talk to Me” (Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes) – but many of the songs would have sounded weak or lacking in ambition had they come out after Born to Run. He seems conscious that he raised the stakes with that album, and that he had to deliver something more than his own versions of “Quarter to Three,” the Gary U.S. Bonds rave-up he often ended his shows with. The good-time songs that end a show aren’t necessarily the ones that people will return to on record, nor are they the ones that will build a legacy.

He was helped in a sense by the legal wrangling he went through as he tried to free himself from his contract with manager Mike Appel. As hard as it was then, it put him in a legal limbo from which he couldn’t release any new material, so he had time to record songs, test ideas and directions, and realize which ones were missteps and which ones were first steps to something more profound.

The earlier versions of “Racing in the Streets” and “Candy’s Boy” (finally released as “Candy’s Room”) are telling not so much in what they are as that he said no to them. On The Promise, “Racing in the Streets” begins with a piano and harmonica that echo the intro to “Thunder Road,” and that linkage makes “Racing in the Streets” sound like a bitter punch line: “How’d that ‘trade in these wings on some wheels’ work out for you, son?” The hope and exhilaration of “Thunder Road” seemingly ends with a guy who knows his car parts better than he knows his girl, and the Mary he coaxed out of the house on Born to Run now sits in the dark “with the eyes of one who hates for just being born.” That kind of symmetry’s tough to turn down, but the more elegiac treatment for the song that he eventually settled on is lonelier but more charitable without offering any false hope.

The difference between “Candy’s Boy” and “Candy’s Room” is even more stark. The airy, strummed version on The Promise has its own dark echo as Danny Federici’s glockenspiel brings “4th of July (Sandy)” to mind. The possibility that the boardwalk life ends with Candy/Sandy turning tricks (or at least having ambiguous relationships with other guys) is a dour one, but that’s not the reason Springsteen laid this one down. The gentle churn of the song is at odds with the narrator’s emotional state, and the song’s about him and his desire, starting with the title. The final version discards two verses and focuses on why he puts up with the uncertainty at all. Musically, the influence of punk that Springsteen mentions in the liner notes is heard most clearly on “Candy’s Room,” where Max Weinberg’s relentless high-hat/snare roll suggests the tension Springsteen suppresses in the spoken verse, a tension that’s exploded when he turns his attention from the circumstances to the one thing he cares about – Candy.

Throughout The Promise, you can hear Springsteen’s record collection as he wrote and recorded genre exercises – girl group songs, party R&B, soul and rockabilly. In the more generic songs, his “Poor Side of Town” identity seems like a pose; in the stronger tracks, he makes it sound real. That he heard the difference and believed in his art to such a degree that he could turn down so many songs that were close-but-no-cigar makes The Promise an engrossing listen, even in the times when the songs alone aren’t. And enough songs are very close, so listening does pay off.