Alfred Elijah Taylor, Sr., the founder of Rosemont Records, was among the first African American studio owners in New Orleans. Mr. Taylot passed away on Wednesday, June 25, 2025 after a long battle with cancer, as reported by his daughter. He was 92 years old.

In May 2011 OffBeat published The Rosemont Records Story by contributor Brice White. The following are excerpts:

Alfred Elijah Taylor was born in 1932 in Mobile, Alabama. He grew up listening from his window to the music of Bishop Phillips at the Church of God in Christ down the street. He was one of three boys and two girls, and after their father died when he was eight-years-old, their mother moved the family back to her hometown of New Orleans. They lived on Touro Street in the Seventh Ward, then moved to 222 N. Tonti, near Canal and Galvez streets. He was in the last class that attended Gilbert Academy on St. Charles Avenue, the first accredited four-year high school for black youth, alongside Ellis Marsalis. When Gilbert Academy closed in 1949, Taylor transferred to McDonogh 35 Senior High School where he became its first drum major. Throughout school, he worked as a drugstore boy at Labranche’s Drugstore on Claiborne Avenue at Orleans, delivering packages on a motorcycle from 5-9 p.m. every night and hustling other odd jobs to help his mother with expenses.

After finishing school, he joined the Air Force and was on active duty from 1952-56 stationed mostly on a mountain-top radio relay station in North Africa. He returned to New Orleans and attended Straight Business College on Claiborne Avenue through the GI Bill, worked for a time as a teletype operator with the Navy, and then trained to be a shortwave radio operator in cargo planes, which he did as a reservist throughout the Vietnam War.

In 1958, he married Martha Tolbert and in 1960 they moved to the newly built Rosemont subdivision on Wilson Avenue in New Orleans East. For Christmas in 1962, his father- in-law, Reverend Alvin Tolbert, gave him a Sony mono portable recorder and asked him to record the annual musical at his church. That was the spark that lit the fire, and after that recording session he was hooked. Taylor started recording the annual musical programs at churches around town using his mono rig and two microphones. He’d set one microphone in front of the choir and one in front of the preacher and live mix the two together as they went to tape.

Naomi Gordon, a gospel singer and friend of Reverend Tolbert, approached Taylor about recording her singing and making it into a record. She cut “He’s Sweet I Know” at the Bright Morning Star Church on Louisiana Avenue, and when it was time to actually get the record pressed, it needed a label. Seeing an opportunity in the market for gospel recordings, Taylor launched Rosemont Records. Churches put a year’s worth of preparation and commitment into their annual musical productions, and it was popular to record the performance and issue it as an LP as a fundraiser for the choir. They were happy to hire Rosemont to record, mix, design, and press their recordings into wax.

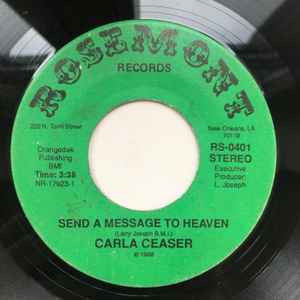

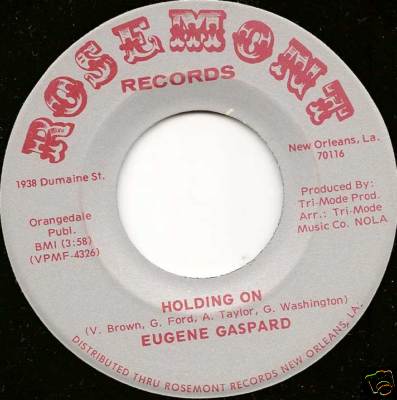

Rosemont’s usual deal was fairly simple. A client paid a set fee for a finished package, usually several thousand dollars for 1,000 LPs or several hundred dollars for 1,000 45s. Rosemont agreed to record and mix down the music and have it pressed onto vinyl, as well as design and print the covers or labels. Usually, the church or individual had no interest in a record label of their own, so it was released on the Rosemont label. Always looking out for the business side of things, Rosemont established its own publishing as well, Orangedale Publishing BMI.

In 1965, Hurricane Betsy hit and flooded out the family’s home. The Taylors rebuilt the house, adding a second floor and a room at the back for a home studio. By 1967, business was going so well that Taylor was driving his wife crazy with the constant noise from the studio. He got an SBA loan tied to Hurricane Betsy recovery and bought 1938 Dumaine Street between Claiborne and Galvez, and it became the home of Rosemont Records for the next 25 years. Taylor renovated the building, built a new studio, and sometime around 1969 upgraded to a four-track stereo tape machine.

While the majority of Taylor’s possessions were lost in Katrina—including most of his archives, master tapes, and back stock—he still has that TEAC four-track. With it, his recording ability upgraded from mono to stereo and from only a single live mix done on the spot to an eight-microphone setup that would be live mixed to four tracks. “I’d put the piano and organ each on one track and the choir on two tracks,” he says. “The soloist would be in the middle of the choir and be picked up by both vocal mics. I’d run eight mics to my eight-channel mixing board, then into the four-track tape machine” Recording this way was an art unto itself as there was quite a bit of sound bleed in live recording, and there was no way to alter what was on each of the four tracks once the recording was finished. Back at the studio, Taylor could remix those four tracks down into the best sound for the final recording, which would be dumped to a two-track tape and sent to Floyd Soileau to be pressed at his Ville Platte Record Manufacturing.

As the popularity of Rosemont Records increased and Taylor became known for his recording ability, his studio became busier and busier. In the mid-1970s, he upgraded to a four-track, half-inch tape console machine for the studio and around 1980, an eight-track, one-inch tape machine.

There were several other gospel labels in the 1960s in New Orleans, including Booker, Wajo, and some national labels releasing local artists, but Rosemont soon outgrew all of them and recorded or released records by a who’s who of the gospel scene, including the Gospel Soul Children, Zion Harmonizers, New Orleans Spiritualettes, the Rocks Of Harmony, Ebenezer Baptist Church Radio Choir, the Melody Clouds, Alvin Bridges and the Desire Community Choir, Thomas J Brown and the Brown Singers, the Crownseekers, the Mighty Chariots, Stronger Hope Baptist Youth Choir, Melvin Spurlock, and literally hundreds more. Many of these groups are still performing to this day and can be seen at Jazz Fest or throughout the year in New Orleans. The biggest hit on Rosemont at the time was “Blessed Assurance” by Reverend Jimmy Olsen, followed by “It’s Amazing” by Sister Geraldine Wright Washington, and “Sit at His Feet and Be Blessed” by Sister Beatrice Lovely.

Rosemont Records’ bread and butter was gospel music, but soon after starting, Al Taylor began to experiment with music in the secular world, releasing blues, soul, funk, disco and eventually rap. Most of these releases were by artists who walked off the street with a song in mind, lyrics, a melody, or just an idea. In the early days, Rosemont would simply record the song for them, but as time went on, Taylor started taking on a producer role, hiring musicians to play rhythm tracks, bringing in backing vocalists, including his three daughters Melinda, Katherine and Susan, and hiring arrangers. Rosemont regularly hired two giants of the New Orleans music scene—each masters of the keys—to collaborate on sessions. Sammy Berfect handled gospel duties, while Willie Tee was in charge of jazz, pop and soul.

In the ’70s and ’80s, Rosemont became a popular place to record political ads and commercials, hosting luminaries from Jessie Jackson to Coretta Scott King to local politicians. During the disco years, Rosemont recorded some legendary, obscure disco 12-inches, including one by blues singer Willie Lee Dixon. Dixon had a particular interest in gorillas and between his original lyrics and music and Willie Tee’s arrangement, “Disco Gorilla” was born. Rudy Mills’ late ’70s act Muchos Plus cut their infamous Caribbean disco 12-inch “Nassau’s Discos” at Rosemont. In 1983, Rosemont released Eric Henderson’s pre-pubescent disco cut “Kids Can Do It Too” as well as Bruce Sampson’s “You’re Bad.”

Sampson was a young man with a great voice from Bogalusa, Louisiana who grew up singing and hanging out after school with the out-of-towners recording at Studio in the Country. In the legendary story of Stevie Wonder driving a car while recording Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants, Bruce Sampson was the teenager in the back seat of the car while Wonder’s assistance guided him by voice around the parking lot of their hotel. Sampson’s parents wanted to help him in his singing career, so when he enrolled at Loyola University in New Orleans, they hooked him up with Rosemont and they set out to produce an R&B hit. Taylor got Chuck Turner and Traffic Jam into the mix, and they recorded the Cameo-style “You’re Bad,” backed with a slow burner called “Stay, Be My Lady.” History was not on their side, and after the beginnings of some radio play the magic fizzled. Only recently has this 12-inch reached legendary status with collectors of the early ’80s funk sub-genre known as boogie music.

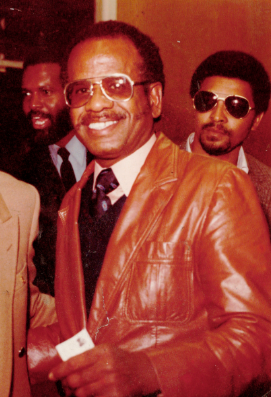

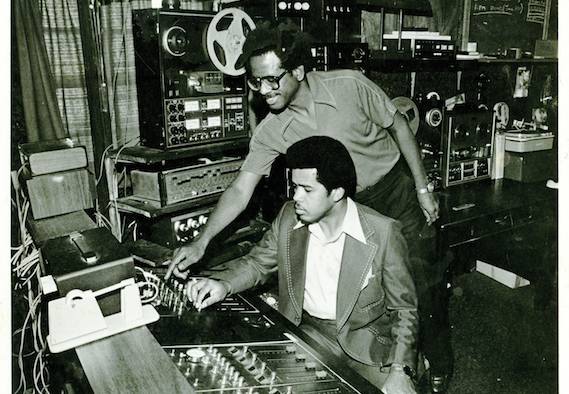

Rosemont Records owner Al Taylor, standing behind Vernard Johnson.

As chronicled in the recent documentary Bury the Hatchet, it was another Rosemont release from 1983 that sparked the split in the Yellow Pocahontas Mardi Gras Indian Tribe, when Victor Harris and several others of the tribe did backing vocals for a Mardi Gras Indian style funk tune, “Shotgun Joe,” by the late Ernest Skipper. Skipper was a well-known figure in the Treme neighborhood, did live sound for bands and festivals, and later formed the Thunder Blues Band. His only vinyl 45, “Shotgun Joe Pt. I & II,” credited background vocals to the Yellow Pocahontas without the blessing of Big Chief Tootie Montana. The Big Chief did not take this lightly, and when the record was released it caused a schism that led Harris and the others involved to create their own Mardi Gras Indian tribe, Fi Yi Yi. Big Chief Harris always gave honor to his original Big Chief, and before Big Chief Montana passed on, the two chiefs reconciled.

As the ’80s moved on, Rosemont issued one of the earliest hip-hop records in the city, “P-Wee’s Beat” by Tonya P, then MC J Ro J “Let’s Jump” and the Famous Low-Down Boys 12-inch “Cold Rockin’ the Place” followed. Always on the move, Taylor also hustled live sound, booked recording acts and bands in and out of town. In 1981 and 1982, he handled live sound engineering and mixing for the Gospel Tent at Jazz Fest.

Taylor recalls that Rev. Avery Alexander was the last person to record a spot in Rosemont Studios before the financial burdens became too high and the payoff too small to keep the studio running, sometime in the early to mid-1990s. Since closing, he received few inquiries into his output or recording legacy until Hurricane Katrina came in 2005 and washed away all the studio records, leftover vinyl, master tapes, and equipment. The evacuation carried Al Taylor to Denver, Colorado, where he lived until this past winter. This will be his first Jazz Fest back as a full-time resident in his hometown, and he’s looking forward to it.

A public second line and a private memorial is planned for later in the year.