New Orleans vocalist Lillian Boutté passed away after a prolonged battle with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease on Friday, May 23, at the age of 75.

Lillian Boutté sang in the Golden Voices Choir as a child and won a singing contest at age 11. She received a bachelor’s degree in music therapy at Xavier University of Louisiana and worked as a session musician in New Orleans.

Lillian Boutté grew up splitting her time between singing gospel in church and R&B in local groups. She saw no conflict between sacred and secular music and mixed gospel with R&B freely. During the 1970s she recorded with Allen Toussaint, James Booker, Patti LaBelle, The Pointer Sisters, The Neville Brothers, Lee Dorsey, Dr. John, Mylon LeFleur and the Olympia Brass Band. She collaborated with the Olympia Brass Band on a gospel record in 1980 and recorded her first jazz album in 1982. She starred in the New Orleans production of the musical One Mo’ Time. The production toured in Europe, where Lillian met her future husband, German reed player Thomas L’Etienne. L’Etienne, an advocate of traditional New Orleans jazz, formed the ensemble Music Friends with Boutté, and Lillian became an international performance and recording star. Though she moved to Germany, Boutté managed to return several times a year to visit her family in New Orleans, and the city honored her with the official title of New Orleans Musical Ambassador, a title that only Louis Armstrong held before her.

In April 2006, only months after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, OffBeat contributor John Swenson interviewed Lillian Boutté. The following are excerpts:

You have a number of musicians in your family, but your parents were not professional musicians.

No. My mom, Gloria, went to work after my dad, George, got sick. My dad was about 50 when he got sick and came into the house and mama went to work then. My dad worked in the post office all his life and he was also a barber all his life. He always worked two jobs.

How did you come to be a musical family?

Because we always had music in school. We had music from kindergarten up, which they don’t do anymore. With 10 kids in the family, we always played with each other. There was always a piano in the house.

My dad’s father would come in and play, and the one thing I always remember is “Salty Dog.” We’d dance to that one. My grandfather on my mother’s side, he was a shake dancer; he would do dancing at the cabaret. By day, he was a longshoreman, a supervisor on the river, and he loved to dance. We always danced and we were always in the pageants. In our schools every May, we had a May pageant.

What happened to your family members after Katrina?

Baby, we got a park—it’s called the Red Bean Shack Trailer Park, [delighted laughter]. Finally, after about five months we got a trailer for my mom, a trailer for my brother and his wife, a trailer for my sister and a trailer for my niece.

I could not sleep until I found out that my mom actually got her trailer. She is the strength of the family. She’s 83. We lost many of our family photos, but there were some I’d saved in plastic zip lock bags in the top part of her closet in the Christmas before last. Best thing in the world to put anything in, baby, is a zip lock bag. My sister went in and was able to take it off of the very top shelf where the water didn’t hit. The most important thing is that everybody’s voice was heard, everybody was found.

Where were you when the hurricane hit?

I was in my house in the countryside, whistling and playing my music, watching the storm approach. On the 27th, I started to worry and called my mother and said, “Mama, maybe you oughtta go by somebody.” She goes, “I’m not going nowhere. I’m staying here!”

So 28 is dire straits. The morning of the 29th, I couldn’t get through to anybody. Meanwhile, I was on call to do some songs for a movie in London and the woman called me and said, “We have a studio for the 30th.” I told her I’d make a ticket, but I had to monitor this storm and see what happens. I only had communication with my sister in Washington and my sister in Atlanta.

John was in Brazil and Tricia was in Norway. But the rest of the family, we didn’t know what happened to them. I couldn’t sleep. I knew Lolet was trapped there. I finally got in touch with John’s friend Gregory, who lived in the French Quarter and had a land line that stayed open. I called Gregory, I was crying, asked him to please find out what happened to mama’s house and tell me she’s not drowned and dead. This boy went through that water and went down there. It was hard for him because there were police everywhere and they weren’t very kind. But he found them and told me they were okay.

Then the flooding really hit and they told people to go to the Superdome, and when I saw the Superdome, I thought I was looking at some third world country. I could not believe that—as people say—when we do all these benefits, that the richest nation in the world would allow this kind of thing to happen. No one would ever dream that this kind of thing would happen to us, what happened in the Superdome and what happened in the Convention Center. I can never ever, ever forget what I was seeing. I wasn’t gonna do this movie soundtrack, but something told me I had to do it, so I had my cell phone with me, told them to keep calling me in the studio.

The commentators on the news were upsetting me because they didn’t know. They were just saying what they could see, and I understood that, especially over in Europe. It was too new to them; they were only listening to what the American commentators were saying. So, I had a friend call the BBC and tell them that New Orleans’ musical ambassador is in town and she’s doing a recording session, and she is really interested in talking about what’s happening. Well, they called right away.

I went on BBC, and I’m looking at our city just completely rolling away from our lives and the people being misplaced, families being separated, husbands and wives sent to one place, kids to another place, just picked out like animals, not even being told where they were going, with no real plan for them. There’s no water in New Orleans; there’s no food going in and they’re calling us looters and shooting us. I’m saying, “Why is somebody not doing something for what’s happening in New Orleans?” They’re showing the French Quarter in the background and this little woman from the BBC asks me very innocently, “Are there no Black people in New Orleans?” I went, “Honey,” I keep screaming at my TV, “Tell me, where’s Chalmette? Where’s Arabi? Where’s St. Bernard? Where are the people?” I saw nothing from there. They didn’t know where I was talking about.

I was in the studio recording these songs for a film called “Nothing But the Blues,” the director is telling me that Whoopi [Goldberg] is in this movie, it’s a big credit, but I’m so overwhelmed from not knowing where my family was. I’m singing this song called “Midnight”—I don’t know how many takes I had to do. All you could hear is me [panting] trying to hold my tears back. The film is about somebody finding something to hold on to while they’re dying, and to see a town die right in front of our eyes, I don’t know how I made it through, but we did it in two days, three songs. For me, it was like a cleansing because I sang what I saw happening in front of my eyes.

But I always kept looking at the light at the end of this tunnel. And I know we’re gonna have that. Right after the storm, people called me saying they would do whatever they could to help. I told them to take time because you cannot tell what people need from what you saw on TV. You cannot just send money because there’s so many bogus things going on. I knew the New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic was the right place. They were getting instruments for the musicians. Send to Tipitina’s. Send to MusiCares.

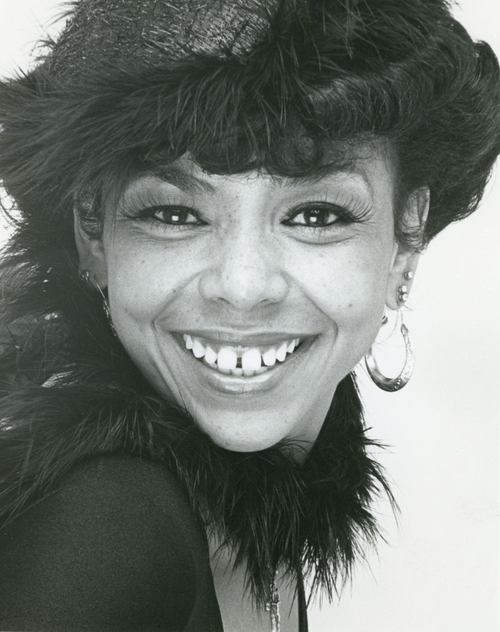

Lillian Boutté performing in 1980. Photo: Syndey Byrd

Have you been back?

I came back for Christmas. When I came off the highway onto Louisiana Avenue, I was driving on my own. I thought I was tough. Closer to the house, I saw the trees and the playgrounds that we played in and Our Lady of Sacred Heart, the church we went to, the grocery store that has been there for generations, then I started to go down Roman [Street] and I was getting sick, but I had to pull myself together and when I came to my mom’s house, it just kind of took me to my knees. Everything was washed away. I just had to let the rest of it go and be happy that everybody’s okay. I couldn’t drive, I was shaking. The tears wouldn’t allow me to drive. I couldn’t see. It was just overwhelming. You just want to get out and do something. What can you do? You can’t do anything but get mad and pray. You don’t let it go this long, not like this, not in America.

It’s like a ghost town there now.

NOT IN AMERICA! Where are the other people in America? What are they thinking? Are they saying, “Well, it’s just New Orleans, Sin City”? I think we got more blessings in that city than anybody could ever believe. Like Little Willie John said, “Let ’em talk if they want to.” But I say to them, look at those pictures on TV of the French Quarter and Jackson Square. Why didn’t that river come over and wash it all away like they wanted to happen? It didn’t. And the river could easily have taken it.

You think they wanted New Orleans to die?

Oooooh, oooooh—what did I say? Wash my mouth out with soap and water [laughing].

They think they’se uprooted it, but it’s there. The first thing I did when went back into town, I went straight to the foot of Canal Street by the cemetery and checked if my dad was still around, to make sure he hadn’t floated off because nobody had been able to check on him yet, and I tell you, he is beautiful. He was right there, not a rock off of it. My mom was happy to know that he had not be desecrated. It was something for me to hold on to.

My dad fought in the war and he was a veteran who didn’t get many things, just as the veterans now are having trouble getting things. They’re cutting things where they don’t belong to be cut, y’understand? I read, I watch the news, I see different news in Europe than they get here, and I know that there are people with their mouths open, but people are not going to go out and protest because they’re gonna come and take ’em away, and then nobody’s gonna know where they are.

And the National Guard had to rescue [people] off the top—now I’m getting mad, okay?—off the roof of their buildings. They claim they didn’t have the helicopters to go in. Excuse me if I call him Chernoble, the National Security man [Homeland Security head Michael Chertoff], when he was on the TV and I was in the studio I was saying, “Where are all these Chinook helicopters?” I stood up and I almost kicked the TV cameraman in his head when Chernoble was asked, “Where are the helicopters?” He said—and I know it was on television; this is not just me—he said, “We cannot call up this service in 24 hours unless it’s a total disaster.” I stood up with the chair, all right? That’s how mad I was. I said ‘Total disaster?! What does he call this?!’, He’s got people on roofs, people dying in the Superdome, people looting, people getting shot and he can’t call them up? I don’t appreciate it. It could have been avoided and it’s not coming out. Why are we taking democracy around the world and not keeping some of it at least at home?

Lillian Boutté was predeceased by her parents, the late George and Gloria LeBlanc-Boutté, and brother Anthony Boutté. She leaves behind sisters Lolet Boutté, Lynette Boutté, Lorna DeLay, Leda Blanks, Lenora Boutté-Hingle; brothers Emanuel Boutté, John Boutté, Peter Boutté; her beloved niece Tanya Ellsworth Boutté, goddaughter Chantell Nabonne and a multitude of nieces, nephews and cousins.

Read the full Lillian Boutté interview here.