We have learned today, July 24, 2025, that Swamp Pop musician, singer songwriter, Tommy McLain has passed away at the age of 85. His family has confirmed the news, saying that “he will live on in his music and songs that he has written and in all of our hearts. We love you and you will be missed greatly missed by all of us.”

Following are excerpts from OffBeat’s September 2022 cover feature on McLain by John Wirt.

In the beginning

Tommy McLain was born March 15, 1940, in the Catahoula Parish town of Jonesville. He was six months old when the family moved to Pineville in Rapides Parish, where his father worked at Camp Beauregard. McLain remembers everyone living in tents and thousands of soldiers coming and going. He also recalls being enraptured by music.

“They would come around the house playing guitars and stuff,” he said. “I was a little-bitty boy. Man, I’d listened to all that and get chills. I loved music.”

McLain sang for people when he was still a small boy.

“Friday or Saturday night, they would throw down,” he said of those house parties. “Everybody would dance, sing. And they put a little box out that I could stand on. ‘Let Tommy sing!’ I was the baby of the family, and I could sing back then.”

The Grand Ole Opry radio broadcasts from Nashville that McLain’s mother let him listen to inspired him, too.

“Ernest Tubb, Faron Young, Kitty Wells and all the singers, I listened to them and figured if they can do that, I can, too. Of course, my older sisters were listening to Hank Williams. I was 12, 13 when he died. I didn’t know why everybody was crazy about him, but he had something about him.”

Left-handed, McLain first played a guitar strung for a right-handed player, turning the instrument upside down. At 12 or 13 he realized he could reverse the strings and play left-handed. “Then my mother got a piano. She should have never done that. I went crazy on that piano.”

McLain performed with professional bands when he was a student at Pineville High School. His father didn’t understand his son’s passion for music.

“He wanted me working, but I intended on playing music,” McLain said. “That’s what God gave me. Even in my teens, I had a great time learning to play, playing in joints, playing for drunks, playing everywhere. If anybody said, ‘Hey, I like your music,’ I’d stay and play.”

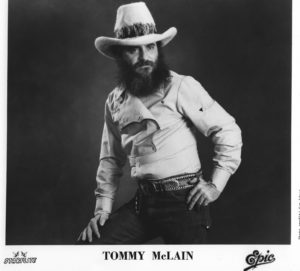

Publicity photo of Tommy McLain

Sweet Dreams

Hearing Patsy Cline’s 1963 recording of “Sweet Dreams” on the radio during a night drive from Monroe to Alexandria, McLain realized that the heartrending torch song that had been a country hit in versions by Cline, Faron Young and Don Gibson would work well for his supper club crowd.

“I thought, ‘That’d be a good tune for my people to dance to. We worked it up. I started doing it my way. All of a sudden, everybody wanted to hear that.”

The enthusiastic response from well-heeled patrons in an Alexandria supper club inspired McLain to record “Sweet Dreams.” He used $500 borrowed from the club’s owner, Ermine Chandler, to pay for a recording session and pressing 500 records.

“Sold out in two or three weeks,” McLain recalled. “And Ms. Chandler called Floyd Soileau in Ville Platte. She said, ‘Tommy McLain from Alexandria has got a hit over here.’”

Soileau, a producer who owned a record shop, label and studio, told British music journalist John Broven that Effie Milligan, owner of the Modern Record Shop in Alexandria, tipped him about McLain’s “Sweet Dreams.” Upon hearing the record Milligan mailed to him, Soileau judged the production inferior. Even so, he heard something special in the performance.

After Soileau unsuccessfully tried to find McLain, the singer showed up in the producer’s studio as bass player with Clint West and the Boogie Kings. At Soileau’s request, McLain re-recorded “Sweet Dreams,” this time with the Boogie Kings’ accompaniment. But Soileau found the new recording lacking, too, and opted not to release it.

“And every time he’d [McLain] come in and do a session with the Boogie Kings,” Soileau told Broven, “Tommy asked me, ‘When are you going to release my record?’ I kept telling him no. … Finally, after saying no so many times, I said, ‘I can’t face this guy anymore. I’m gonna have to put the record out.’”

An unusual endorsement helped the reluctant Soileau see the full potential in McLain’s “Sweet Dreams.” A jukebox operator who stocked records at one of Evangeline Parish’s houses of prostitution told the producer: “That ‘Sweet Dreams’ does not quit playing the jukebox in that house. Them women just play this thing over and over again, and they really know what sells.”

When the regional popularity of “Sweet Dreams” kept growing, Soileau sought national distribution for the record. He contacted Huey P. Meaux, a producer and studio owner in Houston. In turn, Meaux contacted Harold Lipsius, owner of Jamie Records in Philadelphia. Lipsius, Soileau and Meaux subsequently created a new label for McLain’s “Sweet Dreams,” MSL Records. The song’s publisher, Acuff-Rose Music in Nashville, piled in, too, threatening to have Roy Orbison record a cover version of “Sweet Dreams” unless Lipsius and Jamie Records effectively promoted McLain’s record.

When Lipsius finally moved on McLain’s “Sweet Dreams,” sales skyrocketed. Entering the top 20, the record made McLain a star. He appeared on Dick Clark’s “Where the Action Is” TV show and toured with Clark’s “Caravan of Stars.” He shared stages with Otis Redding, the Byrds, Gary Lewis and the Playboys, the Yardbirds and Bobby Vinton.

“Look, I was high dollar,” McClain said. “I was running with Bobby Rydell, Sam the Sham, Chubby Checker. I met Dick Clark. I met all of them. Or maybe I should say they met me. I was on my way up.”

Not equipped for stardom, McLain, like his Louisiana swamp-pop peers Joe Barry, Rod Bernard and Jimmy Donley, sabotaged his career with drink and drugs.

“I went crazy,” he said. “Hey, son, I got my hands on that money and started doing everything I wanted to do. I became a little god. I wasn’t educated enough to do right.”

McLain shared details of his wasted days and nights with Shane Bernard, author of Swamp Pop: Cajun and Creole Rhythm and Blues.

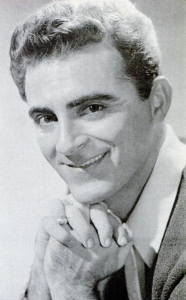

Photo from advertisement in Billboard, page 39, September 1966. From Wikipedia

“…’66 and ’67, I barely remember, because I was on a plane going somewhere every weekend for a couple of years. I was everywhere. If I wasn’t on an airplane, I was on a tour bus. And I was eating speed like candy and taking sleeping pills … I started going downhill faster than I went up.”

He got in tax trouble, too.

“I never had seen that kind of money,” he said. “So here comes the income tax man. Just like Willie Nelson and all of them. I did the same thing. And that income tax scared the pee out of me. They put a stop on my money. And then I had to go back down to the bottom.”

McLain ultimately survived stardom and his steep fall from fame, converting to Catholicism and changing his ways.

“I’m a Catholic evangelist,” he said recently in Plaucheville. “I don’t even drink a beer. Don’t want it. I wish cocaine could pay me back for what I spent on it. Why I did all that, I don’t know. It wasn’t worth it. The time you think about that is time you lose playing music.”

His national career essentially over in 1968, McLain regrouped a few years later, forming his Muletrain Band and carrying on as a regional attraction. In the 1970s, he recorded many singles for Meaux’s Crazy Cajun label and, in 1979, released the Meaux-produced album Backwoods Bayou Adventure via major label Epic Records.

Running down a dream

In 2019, Adcock and McLain, hoping to secure a recording contract, brought McLain’s new songs to Austin’s South By Southwest Music Festival.

“The guy from Decca Records in England walked in,” Adcock said. “We got a deal. It couldn’t have been going more storybook. We thought were on top of the world that summer—but then the wheels came off real quick. Tommy had a massive heart attack. We hid that from the record company, so they wouldn’t drop him.”

McLain recovered, but then the coronavirus pandemic posed its formidable challenges. McLain and Adcock worked on the album anyway, under challenging, distanced circumstances in Mike Napolitano’s studio. As the pandemic dragged on, hurricanes and a deep freeze ravaged McLain’s part of Louisiana.

In January 2021, another disaster struck when Decca Records dropped McLain. “I didn’t even know how to tell Tommy,” Adcock lamented. Fortunately, Yep Roc Records picked the album up, making it a priority.

There would be even more trials before I Ran Down Every Dream became reality. A scheduled release for the album in October 2021, concurrent with the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, didn’t materialize because Jazz Fest was canceled again due to the ongoing pandemic. A few months later, an arsonist burned McLain’s house in Oakdale down.

“Some arsonist come through, having a ball,” McLain said. “I’m glad I wasn’t in there. Because I used to drink and smoke and do a little drugs, brother. What if I’d been in there passed out, son? Poof.”

Law enforcement caught the arsonist, but McLain declined to press charges. “I couldn’t press charges against nobody, man,” he said. “I wasn’t going back to Oakdale anyway. That’s the way I am. I’m a free spirit. I’m going to pick up them bags and be gone right now. I never did like to be held down.”

After the fire, McLain sold his seven acres in Oakdale and moved to Plaucheville, which is closer to his adult children and just a bayou drive away from Adcock in Lafayette. It’s helpful, too, that Plaucheville’s peacefulness is good for McLain’s songwriting.

“I like to be with myself when I’m writing,” he said. “Sometimes it drives me crazy to write. I stagger over words. And I’ve got to go back and make sure I did the right words and said that line right. But sometimes when Charles and I play somewhere, I’ll write a tune before we get back to the house. Other times it takes me years. I’ll get a line or two—the hook they call it—and that goes on and on. And sometimes I’ll wake up and there it is—the whole thing comes together. It’s a different kind of work, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

“It makes me young. I’m going to play ’till God takes me away.”

I Ran Down Every Dream

Fifty-six years after “Sweet Dreams,” the 82-year-old singer is in the national spotlight again. His new album is the fullest artistic statement of his career. I Ran Down Every Dream features original songs composed by McLain, Elvis Costello, Nick Lowe and the singer’s principal collaborator and sidekick, Lafayette producer-guitarist Charles “C.C.” Adcock.

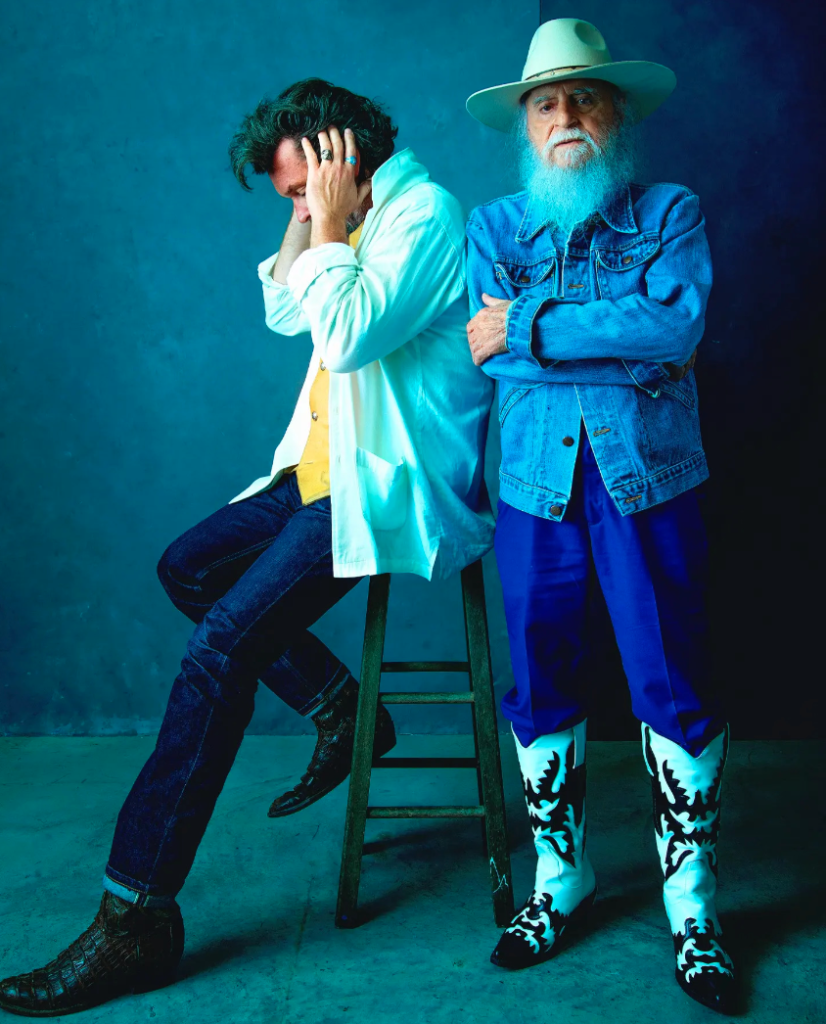

C.C. Adcock and Tommy McLain

In May 2025, McLain and Adcock made a guest appearance during Costello’s headlining show at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. They joined the British star for performances of McLain’s swamp-pop classics “Sweet Dreams” and “Before I Grow Too Old.” Costello, a McLain fan, recorded “Sweet Dreams” for his 1981 album, Almost Blue. Four decades later, he’s co-written two songs for I Ran Down Every Dream and he’s a guest vocalist for the title track.

“Tommy McLain,” Costello says in McLain’s latest bio, “has just made one of the greatest records you’d ever imagine. My friend C.C. Adcock did a great job as producer. It’s an absolute masterpiece. With Tommy, you are going to hear a man singing from his soul, a beautiful, beautiful man. He’s one of the great unsung heroes of American vocalizing, and he still sounds as good as he did when he cut ‘Sweet Dreams’ in 1966.”

Nick Lowe, another of McLain’s noted English fans, co-wrote “The Greatest Show on Hurt” for McLain’s album. Lowe also selected the McLain-Adcock duo as opening act for the Quality Rock & Roll Revue, the summer tour headlined by Lowe and featuring Los Straitjackets. The size of the tour’s venues—large clubs and small theaters—suits McLain fine.

“The closer you can be to the audience, the better I like it,” he said some weeks ago at his home in the quiet Avoyelles Parish village of Plaucheville. “I’m a storyteller. If I can get my story across, you experience the same thing I did.”

He was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame in 2007. McLain was the subject of profiles in OffBeat Magazine, the New York Times, NPR and Rolling Stone among others, and performed on the James Corden Show.

McLain is survived by his children Barry McLain (Phyllis) of Crowley, David McLain (Amie) of Mansura, Felecia Soileau (William) of Cottonport, Chad McLain (Nikki) of Cottonport, Jonathan McLain (Julia) of Pride, and Alyson Lemoine (Guy) of Plaucheville. He is also survived by his 10 grandchildren, 7 great-grandchildren, and 1 great-great-grandchild; and his significant other, Carol Skaggs.

Funeral Mass for Tommy McLain will take place at the St. Mary’s Assumption Catholic Church of Cottonport on Monday, July 28th, 2025 beginning at 10 a.m. Burial will take place at the St. Mary Catholic Cemetery #2.

Escude Funeral Home of Cottonport, 552 Front St. Cottonport, LA 71327 (318-964-2324) has been entrusted with the funeral arrangements.