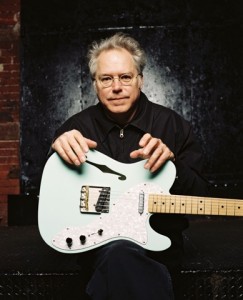

Simply put, guitarist Bill Frisell is a master of the sonic landscape—a virtuoso of both timbre and texture. Though rooted in jazz, the breadth of Frisell’s work spans the genres of blues, folk, rock, country, world, chamber, and classical music. Over the course of his professional career, dating back to the early ’80s, Frisell has released more than 40 albums, in addition to serving as a sideman on countless others. His collaborative output outside of the jazz world is just as impressive. Names such as Elvis Costello, Lucinda Williams, Paul Simon, Brian Eno, Vernon Reid, Norah Jones, and Loudon Wainwright are just a few of his co-conspirators.

His ironically titled, Grammy-winning album Unspeakable (2004) perhaps best captures what has made Frisell one of the most significant musicians of his era—a sound which is as identifiable as it is illusive and as unforgettable as it is indefinable. It is hardly a matter of conjecture to say that he is one of the most expressive players to ever pick up a guitar. Fresh off of the release of four projects in five months, OffBeat had a chance to speak with the soft-spoken guitarist as he prepared for an upcoming swing along the Mississippi River, stopping at Snug Harbor this Saturday, May 7.

So far 2011 has been a big year for you. It’s only May, and you’ve already released Lagrimas Mexicanas and Sign of Life yourself as well as The Majestic Silver Strings with Buddy Miller and City of Refuge with Abigail Washburn, albums that are all very different from each other.

Yeah (small chuckle), I don’t know what’s happened. I’ve just been so busy. It’s hard for me to keep track of myself.

Let’s talk about your album with Vinicius Cantuaria, Lagrimas Mexicans, first. You two previously worked together on The Intercontinentals (2003), right?

Actually, we’ve known each other for a really long time. I had played on two or three of his album before The Intercontinentals. It’s been—oh, boy—maybe 20 years that we’ve know each other.

Where did the concept for a duets record come from?

We had been talking about it for a long, long time (pauses, laughs), and then it took a really long time for us to get together at the same place. Even before The Intercontinentals we had done some duo gigs. So, the seeds had been planted back then. Every time we play, it’s just been so effortless. The music always seems to pour out of him. All I have to do, really, is go along for the ride.

Moving on to Sign of Life, what was the impetus to release another album with the 858 Quartet?

Well, we first got together to do this project (Richter 858) inspired by these Gerhard Richter paintings—whenever that was (2005). That’s what got us going, but we’ve played a lot since then. The music really grew out of that and kept changing and changing. I wanted to have some sort of document of where we were at right now. We’ve been a band all along, and we are a touring band too, but we didn’t have any real, current music that was documented.

What was really unusual for me about that record was that I went to this place called the Vermont Studio Center. Mainly, painters and writers go there. It’s like a big artist retreat place way up in northern Vermont. I stayed there for a month and wrote music everyday. Those guys (the 858 Quarter) came up there at the end of that time. We sifted through some of the stuff I had written, and we recorded it right after that.

Knowing the story behind Richter 858, it’s interesting to hear how you were inspired by the painters and writers at the conservancy this time. When I first listened to Sign of Life, it struck me as a series of suites drawn together under a larger theme.

In all fairness, I don’t know if I’ve ever done anything where all the music came from one particular place. Usually when I do an album, I grab stuff from all over the place. This is the most concentrated album of my career. It’s definitely the only one where all of the music came from one time zone (laughs).

I was first introduced to your music when a co-worker gave me a copy of Gone, Just Like a Train (1998). Now I have at least 10 of your albums, and I consider myself an avid fan. But looking at your output, sometimes I feel like I’m just scratching the surface. What sort of things have guided you through the different phases of your career?

For me, it’s something that I never really have to think about. That’s what I enjoy about music. It just sort of pulls me. I don’t even have to think about where to go next. Everyday, I see things, or I come across something, and I think, “Oh my God, I gotta check this out, or I gotta do this!” It’s not a very calculated thing. I don’t really have a big plan or anything. It’s like I’m in this amazing world where things just keep appearing in front of me—challenges. It’s really been like that my whole life.

One aspect of your career that I’ve always been intrigued by is your collaborations outside of world of jazz. You’ve got this new album with Buddy Miller, and I remember a few years ago hearing you on Paul Simon’s Surprise (2006). You’ve done work for films and art installations and essentially, with more people and across more genres than I can count.

Now, I’m 60 years old (laughs); I’ve been playing a long time. But I never really aggressively tried to promote myself. I just started playing, and one thing lead to another. You meet one person, and then they know somebody. That’s really how I learn. The thing inspires me the most is being with all these different musicians.

When I first got a guitar, I had a friend down the street who had a guitar. And then one of us had a friend who played drums and the other, a friend who played bass. It’s like a chain reaction. It just starts happening. If you’re open, you just keep meeting new people. I really love all kinds of music, and I thrive on playing with all kinds of different people.

Listening to you describe your connection to music and your openness to explore and develop relationships with other musicians, your connection to Vic Chestnutt, whom you previously recorded with and recently dedicated the song “Better Than a Machine” (Beautiful Dreamers, 2010) to, instantly comes to my mind. Can you tell me a little bit about your relationship with him?

I met Vic with another guy that’s been really important to me, Hal Willner, who produced my Unspeakable album. Also, some of the first recordings I ever did were with Hal in the early Eighties. Hal introduced me to Vic at a concert of Randy Newman music. That was the first time I played with Vic. We sort of connected, and I invited him to come to these concerts I was doing in Germany (the Century of Song series) featuring different songwriters. There, we really got to play a lot of his songs as well as songs that had inspired him. After that, he asked me to play on one of his albums (Ghetto Bells, 2005). We ended up becoming good friends. Whenever I’d go to Athens, we’d play together there. He was truly an amazing musician and just an amazing person.

So tell me about this album you just did with Buddy Miller, The Majestic Silver Strings.

Actually, Buddy came to that same thing in Germany. I asked him to be a part of it too. That might have been the first time we really (stops)—no, we first met years ago on a radio show in Boulder, Colorado when he was playing with Emmylou Harris. I had also known of his music before that, and I really loved his stuff. Gradually, we started talking and ending up doing more together. Then, recently, there was this moment where I asked him to produce a record. I just wanted to do something with him. So the idea had been floating around. Then he met Marc Ribot (guitar), and I had played a lot with Marc in the past, and we had all played a lot with Greg Leisz (guitar), too. Then, it all sort of exploded suddenly. The idea was to do these older, country songs but to give the guitars a lot of room. It was amazing doing the recording at Buddy’s house.

Did the vocalists do their takes after you guys laid down the tracks?

No, we were just all there in a room, recording everything at the same time.

Listening to the album today, how does it compare to the vibe of the sessions?

I’m totally happy with it. We’ve been able to do a couple gigs, and what really stands out to me is how we’re able to go into so many other things live.

It’s a shame because Buddy was in town last week playing in Robert Plant’s band. You guys just missed each other.

Oh, man. He was just in Seattle a few days ago, and I wasn’t home. I wish I could see those guys.

Well, I’m looking forward to your show at Snug Harbor on Saturday. What do you have in store? It’s a rare treat for you to be in New Orleans.

I’ll be playing with a group of guys that I’ve played with forever: Ron Miles on trumpet, Tony Scherr on bass, and Kenny Wollesen on drums. It’s actually the beginning of a new project I’m working on with filmmaker Bill Morrison. It’s kind of heavy that we’re playing in New Orleans because he’s doing a film using old footage from the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927. I’m doing the music for that with these guys, so we’re starting from New Orleans and going to Oxford and then to St. Louis—all the way up the Mississippi River as we work on this music.